This talk was delivered at MIT for Justin Reich’s Comparative Media Studies class “Learning, Media, and Technology.” The full slide deck is available here.

Thank you for inviting me to speak to your class today. I’m really honored to be here at the beginning of the semester, as I’m not-so-secretly hoping this gives me a great deal of power and influence to sow some seeds of skepticism about the promises you all often hear – perhaps not in this class, to be fair, as in your other classes, in the media, in the world at large – about education technology.

Those promises can be pretty amazing, no doubt: that schools haven’t changed in hundreds if not thousands of years and that education technology is now poised to “revolutionize” and “disrupt”; that today, thanks to the ubiquity of computers and the Internet (that there is “ubiquity” is rarely interrogated) we can “democratize,” “unbundle,” and/or “streamline” the system; that learning will as a result be better, cheaper, faster.

Those have always been the promises. Promises largely unfulfilled.

It’s important – crucial even – that this class is starting with history. I’ve long argued that ignorance of this history is part of the problem with education technology today: that its promises of revolution and innovation come with little to no understanding of the past – not just the history of what technologies have been adopted (or have failed to be adopted) in the classroom before, but the history of how education itself has changed in many ways and in some, quite dramatically, with or without technological interventions. (I’d add too that this is a problem with tech more broadly – an astounding and even self-congratulatory ignorance of the history of the industries, institutions, practices folks claim they’re disrupting.)

I should confess something here at the outset of my talk that’s perhaps a bit blasphemous. I recognize that this class is called “Learning, Media, and Technology.” But I’m really not interested in “learning” per se. There are lots of folks – your professor, for starters – who investigate technology and learning, who research technology’s effect on cognition and memory, who measure and monitor how mental processes respond to tech, and so on. That’s not what I do. That’s not what my work is about.

It’s not that I believe “learning” doesn’t matter. And it’s not that I think “learning” doesn’t happen when using a lot of the ed-tech that gets hyped – or wait, maybe I do think that.

Rather, I approach “learning” as a scholar of culture, of society. I see “learning” as a highly contested concept – a lot more contested than some researchers and academic disciplines (and entrepreneurs and journalists and politicians) might have you believe. What we know about knowing is not settled. It never has been. And neither neuroscience nor brain scans, for example, move us any closer to that. After all, “learning” isn’t simply about an individual’s brain or even body. “Learning” – or maybe more accurately “learnedness” – is a signal; it’s a symbol; it’s a performance. As such, it’s judged by and through and with all sorts of cultural values and expectations, not only those that we claim to be able to measure. What do you know? How do you know? Who do you know? Do you have the social capital and authority to wield what you know or to claim expertise?

My work looks at the broader socio-political and socio-cultural aspects of ed-tech. I want us to recognize ed-tech as ideological, as a site of contested values rather than a tool that somehow “progress” demands. Indeed, that’s ideology at work right there – the idea of “progress” itself, a belief in a linear improvement, one that’s intertwined with stories of scientific and technological advancement as well as the advancement of certain enlightenment values.

I’m interested not so much in how ed-tech (and tech more broadly) might change cognition or learning, but in how it will change culture and power and knowledge – systems and practices of knowing. I’m interested in how ed-tech (and tech more broadly) will change how we imagine education – as a process, as a practice, as an institution – and change how we value knowledge and expertise and even school itself.

I don’t believe we live in a world in which technology is changing faster than it’s ever changed before. I don’t believe we live in a world where people adopt new technologies more rapidly than they’ve done so in the past. (That is argument for another talk, for another time.) But I do believe we live in an age where technology companies are some of the most powerful corporations in the world, where they are a major influence – and not necessarily in a positive way – on democracy and democratic institutions. (School is one of those institutions. Ideally.) These companies, along with the PR that supports them, sell us products for the future and just as importantly weave stories about the future.

These products and stories are, to borrow a phrase from sociologist Neil Selwyn, “ideologically-freighted.” In particular, Selwyn argues that education technologies (and again, computing technologies more broadly) are entwined with the ideologies of libertarianism, neoliberalism, and new forms of capitalism – all part of what I often refer to as the “Silicon Valley narrative” (although that phrase, geographically, probably lets you folks here at MIT off the hook for your institutional and ideological complicity in all this). Collaboration. Personalization. Problem-solving. STEM. Self-directed learning. The “maker movement.” These are all examples of how ideologies are embedded in ed-tech trends and technologies – in their development and their marketing. And despite all the talk of “disruption”, these mightn’t be counter-hegemonic at all, but rather serve the dominant ideology and further one of the 21st century’s dominant industries.

I want to talk a little bit today about technology and education technology in the 20th century – because like I said, history matters. And one of the ideological “isms” that I think we sometimes overlook in computing technologies is militarism. And I don’t just mean the role of Alan Turing and codebreakers in World War II or the role of the Defense Department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency in the development of the Internet (although both of those examples – cryptography and the Internet – do underscore what I mean when I say infrastructure is ideological). C3I – command, control, communications, and intelligence. Militarism, as an ideology, privileges hierarchy, obedience, compliance, authoritarianism – it has shaped how our schools are structured; it shapes how our technologies are designed.

The US military is the largest military in the world. That also makes it one of the largest educational organizations in the world – “learning at scale,” to borrow a phrase from this course. The military is responsible for training – basic training and ongoing training – of some 1.2 million active duty soldiers and some 800,000 reserve soldiers. That training has always been technological, because soldiers have had to learn to use a variety of machines. The military has also led the development and adoption of educational technologies.

Take the flight simulator, for example.

One of the earliest flight simulators – and yes, this predates the Microsoft software program by over fifty years, but postdates the Wright Brothers by only about twenty – was developed by Edwin Link. He received the patent for his device in 1931, a machine that replicated the cockpit and its instruments. The trainer would pitch and roll and dive and climb, powered by a motor and organ bellows. (Link’s family owned an organ factory.)

Although Link’s first customers were amusement parks – the patent was titled a “Combination training device for student aviators and entertainment apparatus” – the military bought six in June of 1934, after a series of plane crashes earlier that year immediately following the US Army Air Corps’ takeover of US Air Mail service. Those accidents had revealed the pilots’ lack of training, particularly under night-time or inclement weather conditions. By the end of World War II, some 500,000 pilots had used the “Link Trainer,” and flight simulators have since become an integral part of pilot (and subsequently, astronaut) training.

(There’s a good term paper to be written – you are writing a term paper, right? – about the history of virtual reality and the promises and presumptions it makes about simulation and learning and experiences and bodies. But mostly, I’d argue if I were writing it, that much of VR in classrooms today does not have its origins the Link Trainer as much as in the educational films that you read about in Larry Cuban’s Teachers and Machines. But I digress.)

The military works along a different principle for organizing and disseminating knowledge than does, say, the university or the library. The military is largely interested in teaching “skills.” Or perhaps more accurately, this is how military training is largely imagined and discussed: “skills training.” (Officer training, to be fair, is slightly different.) The military is invested in those skills – and in the teaching of those skills – being standardized. All this shapes the kinds of educational software and hardware that gets developed and adopted.

One of the challenges the military has faced, particularly in the twentieth century, is helping veterans to translate their skills into language that schools and civilian hiring managers understand. This is, of course, the origin of the GED test, which was developed during WWII as a way to assess whether those soldiers who’d dropped out of high school in order to enlist had attained high-school level skills – to demonstrate “competency” rather than rely on “seat time,” to put this in terms familiar to educational debates today. There has also been the challenge of translating skills within the military itself – say, from branch to branch – and within and across other federal agencies. New technologies, to a certain extent, have complicated things by introducing often incompatible software systems in which instruction occurs. And at the end of the day, the military demands regimentation, standardization – culturally, technologically.

I just want to lay out an abbreviated timeline here to help situate some of my following remarks:

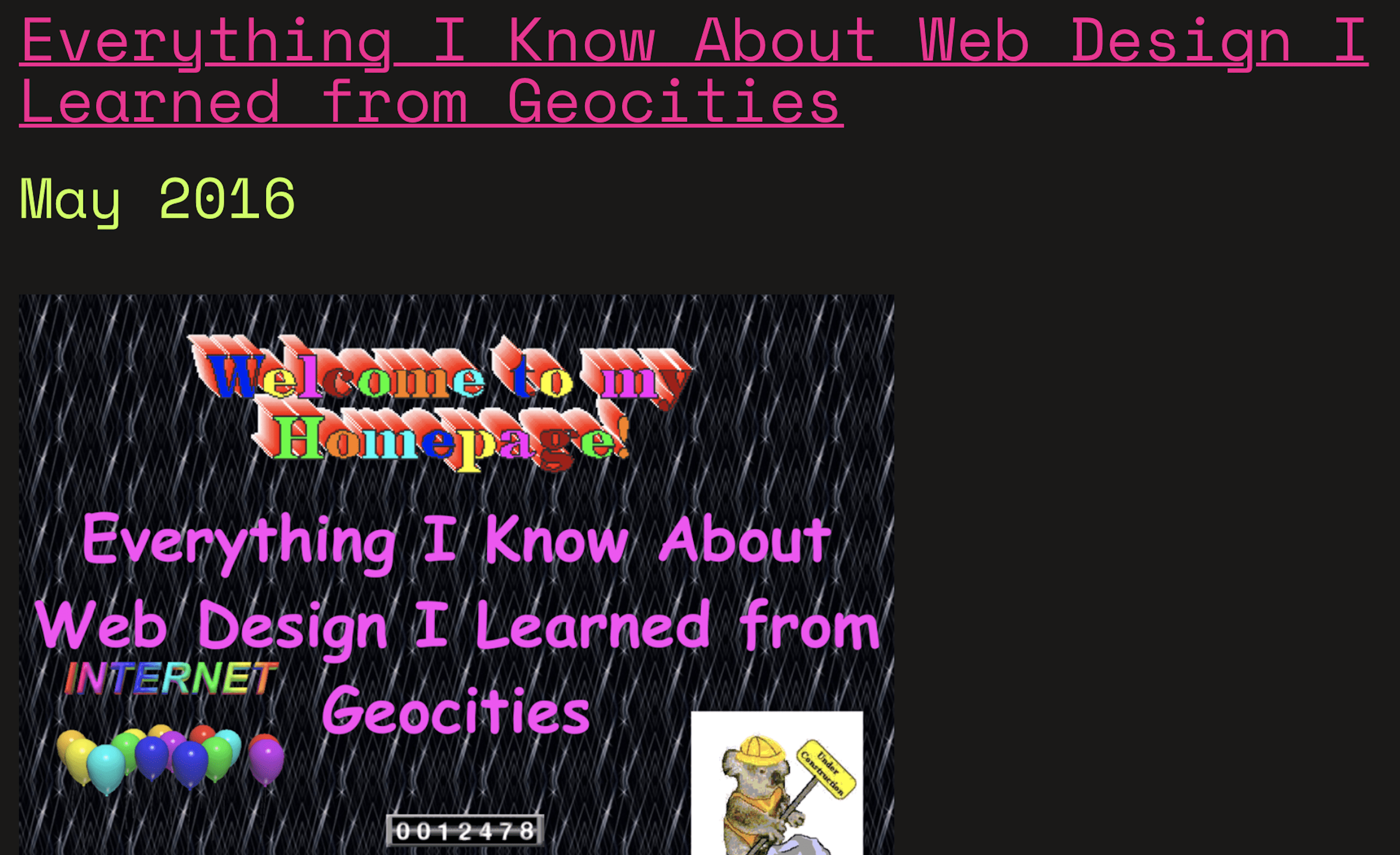

I’m not suggesting here that the Web marks the origins of ed-tech. Again, you’ve read Larry Cuban’s work; you know that there’s a much longer history of teaching machines. But in the 1990s, we did witness a real explosion in not just educational software, but in educational software that functioned online.

In January of 1999, President Clinton signed Executive Order 13111 – “Using Technology To Improve Training Opportunities for Federal Government Employees.” Here’s the opening paragraph, which I’m going to read – apologies – simply because it sounds as though it could be written today:

Advances in technology and increased skills needs are changing the workplace at an ever increasing rate. These advances can make Federal employees more productive and provide improved service to our customers, the American taxpayers. We need to ensure that we continue to train Federal employees to take full advantage of these technological advances and to acquire the skills and learning needed to succeed in a changing workplace. A coordinated Federal effort is needed to provide flexible training opportunities to employees and to explore how Federal training programs, initiatives, and policies can better support lifelong learning through the use of learning technology.

One of the mandates of the Executive Order was to:

in consultation with the Department of Defense and the National Institute of Standards and Technology, recommend standards for training software and associated services purchased by Federal agencies and contractors. These standards should be consistent with voluntary industry consensus-based commercial standards. Agencies, where appropriate, should use these standards in procurements to promote reusable training component software and thereby reduce duplication in the development of courseware.

This call for standards – and yes, the whole idea of “standards” is deeply ideological – eventually became SCORM, the Sharable Content Object Reference Model (and one of the many acronyms that, if you work with education technology, will make people groan – and groan almost as much as a related acronym does: the LMS, the learning management system).

Indeed, SCORM and the LMS – their purposes, their histories – are somewhat inseparable. (And I want you to consider the implications of that: that the demands of the federal government and the US military for a standardized “elearning” experience has profoundly shaped one of the foundational pieces of ed-tech that is used today by almost all colleges and increasingly even K–12 schools.)

The SCORM standard was designed, in part, to make it possible to easily move educational content from one learning management system to another. Among the goals: reusability, interoperability, and durability of content and courses. (I’m not going to go into too much technical detail here, but I do want to recognize that this did require addressing some significant technical challenges.) SCORM had three components: content packaging, runtime communications, and course metadata. The content packaging refers to the packaging of all the resources needed to deliver a course into a single ZIP file. The runtime communications includes the runtime commands for communicating student information to and from the LMS, as well as the metadata for storing information on individual students. And the course metadata, obviously, includes things like course title, description, keywords, and so on. SCORM, as its full name implies, served to identify “sharable content objects” – that is the smallest unit in a course that contains meaningful learning content by itself – content objects that might be extracted and reused in another course. The third version of SCORM, SCORM 2004, also introduced sequencing, identifying the order in which these content objects should be presented.

The implications of all this are fairly significant, particularly if we think about the SCORM initiative as something that’s helped, almost a decade ago, to establish and refine what’s become the infrastructure of the learning management system and other instructional software, as something that’s influenced the development as well of some of the theories of modern instructional design. (Theory is, of course, ideology. But, again, so is infrastructure.) The infrastructure of learning software shapes how we think about “content” and how we think about “skills” and how we think about “learning.” (And “we” here, to be clear, includes a broad swath of employers, schools, software makers, and the federal government – so that’s a pretty substantial “we.”)

I will spare you the details of decades worth of debates about learning objects. It’s important to note, however, that there are decades of debate and many, many critics of the concept – Paulo Freire, for example, and his critique of the “banking model of information.” There are the critics too who argue for “authentic,” “real-world” learning, something that almost by definition learning objects – designed to move readily from software system to software system, from course to course, from content module to content module, from context to context – can never offer. I’d be remiss if I did not mention the work of open education pioneer David Wiley and what he has called the “reusability paradox,” which to summarize states that if a learning object is pedagogically useful in a specific context, it will not be useful in a different context. Furthermore, the most decontextualized learning objects are reusable in many contexts, but those are not pedagogically useful.

But like I said at the outset, in my own line of inquiry I’m less interested in what’s “pedagogically useful” than I am in what gets proposed by industry and what becomes predominant – the predominant tech, the predominant practice, the predominant narrative, and so on.

Learning objects have been blasted by theorists and practitioners, but they refuse to go away. Why?

The predominant narratives today about the future of learning are all becoming deeply intertwined with artificial intelligence. We should recognize that these narratives have been influenced by decades of thinking in a certain way about information and knowledge and learning (in humans and in machines): as atomized learning objects and as atomized, standardized skills.

There’s a long history of criticism of the idea of “intelligence” – its origins in eugenics; its use as a mechanism for race- and gender-based exclusion and sorting. It’s a history that educational psychology, deeply intertwined with the development of measurements and assessments, has not always been forthright about. Education technology, with its origins in educational psychology, is implicated in this. And now we port this history of “intelligence” – one steeped in racism and bias – onto machines.

But we’re also porting a history of “skills” onto machines as well. This is, of course, the marketing used for Amazon’s Alexa. Developers “build” skills. They “teach” skills to the device. And it’s certainly debatable whether many of these are useful at all. But again, that’s not the only way to think about teaching machines. Whether or not something is “pedagogically useful,” here are reasons why the stories about it stick. The narrative about AI and skills is something to pay attention to – particularly alongside larger discussions about the so-called “skills gap.”

from Hack Education http://ift.tt/2jvnUGS

via IFTTT